When Fashion Sells Feminism

A funny thing has happened in fashion over the past several years. Where once the industry proved itself as a leader willing to embrace new ideas while tackling weathered barriers, it now seems to be a consistent grasper of straws. Slumping sales, changing markets, shifting demographics and digital innovation have all played a part in fashion’s consistent fumbling. In the hope that it will strike a financial motherload, the fashion industry often looks to movements outside its own walls that it can appropriate in the most superficial way possible in order to gain positive coverage and join the media fray as it struggles to maintain relevancy. Sadly, the renewed interest in feminist ideals is the latest target of luxury’s vampiric feeding. As a man, I would never claim to fully comprehend the countless nuances surrounding womanhood, but the glaring inconsistencies promoted by the fashion machine are simply too disturbing not to notice.

Though there are many brands churning out what they can to feign interest in a genuinely important cultural conversation, the most egregious example of jumping on the feminist bandwagon is undoubtedly Maria Grazia Chiuri’s Dior. Chiuri has a long history of making questionable choices when it comes to representation in her work. Remember that Africa-inspired Spring/Summer 2016 Valentino collection shown in 2015 that had nearly 90 looks yet only a handful of black models? True, it was designed with Pierpaolo Piccioli, who remains Valentino’s creative director, but that brand has become noticeably more international in look and feel since Chiuri’s departure while Dior’s catwalk lineup will include, at best, a light spattering of models of color. It also doesn’t help that her casting skews incredibly young and frighteningly thin, even by fashion standards. Yes, these criticisms could be leveled at countless labels, and while they should most definitely be held to account by the public, those brands don’t claim feminism as a banner cause as Chiuri has.

In a move that I’m sure both Chiuri and her publicity team hoped would be an Instagrammable moment, her debut runway show for the house of Dior in September of 2016 featured a t-shirt emblazoned with the statement, “We Should All Be Feminists,” in black type against a simple white background. With the U.S. presidential campaign reaching a boiling point and issues specific to women at the fore, Chiuri’s appointment seemed like a much-needed antidote as the start of her tenure marked the first time any woman has ever headed the venerable French couture house of Christian Dior. She made feminist themes a pillar of her debut, drawing much of her inspiration from official fencing attire, one of, if not the only, sport where men and women don identical uniforms. Many of the same problems that emerged at Valentino were still evident: people of color were reduced to tokenism, the age cutoff couldn’t have been far past typical high school graduation, and there were practically no variations in body type whatsoever.

But let’s set those issues aside for a moment to consider the clothes alone. That first collection, with its heavily worked fencing inspiration, resulted in a host of heavily padded, awkwardly fitted jackets and vests that skewed a bit more asylum than Olympic arena. Add to those sheer silk blouses and equally transparent skirts layered over shorts that ended just past the gluteal fold and you have a collection filled with deeply impractical, unflattering clothes that are particularly unkind to anyone over 30--something that makes even less sense when considering the age of the average, moneyed Dior shopper.

Chiuri was clearly aware of the weight of her new role as one of the few women in a leadership position in the industry, but has not done anything since to make her clothes friendly to the wearer. It goes to show that the old platitude insisting female designers create clothes while male designers create costumes is an untrue and lazy criticism. As Pulitzer Prize-winning fashion journalist Robin Givhan noted in her review of Dior’s Spring/Summer 2018 collection (which was partially inspired by art historian Linda Nochlin’s scholarship), “Perhaps a more ambitious or daring designer would have found a way [to address important feminist issues]. Fashion, after all, has been used to express a range of emotions from sorrow and anger to giddy delight. Instead, Chiuri uses feminism as an overlay or a gloss. That isn’t to say that she doesn’t believe deeply in the issues...But she has reduced them to slogans and backdrop. Their meaning is not carried through in the garments themselves.”

Greats of the past have shown an enormous aptitude for physicalizing a specific response to their times. There’s good reason that someone like Coco Chanel is so revered. The legendary French fashion designer definitely did her best to canonize herself in life, but it is the poetic practicality of her clothes that has survived her in death. Discussion of any kind of diversity when speaking of her era is almost moot as there was practically none in fashion, but the philosophy behind her garments continues to resonate despite her more than problematic (and opportunistic) affiliations, like those with officers of the Third Reich.

Chanel wanted women to have the female equivalent of a man’s suit—something that could take you from a social function to church to work to dinner, and everywhere in between. The Chanel suit is something that can be thrown on without thought and still result in a polished ensemble. A jacket, a skirt, maybe a silk blouse and the right accessory. Done. It was chic by numbers and it worked because sometimes there’s nothing more liberating than a uniform. There was an athleticism, a briskness to the composition that let any onlooker know the Chanel women was on the move. It was a rare ideology during couture’s golden age and remains shockingly absent in the present day, but there are most definitely other creatives in recent memory who did not rely on catchphrases to connote their intentions.

Martin Margiela is recognized as a Belgian radical whose oeuvre continues to find new life as people inspired by his work, such as Raf Simons, become ever larger, more important cultural figures. His signature aesthetic is resolutely avant-garde, but not only in the sense that might first spring to mind. Margiela’s work can seem whacky on the surface—dresses made from flea market-sourced wedding gowns, tops crafted from a patchwork of vintage leather gloves—and much of it certainly can be, however, his work for Hermès revealed his deeper, and ingenious, sensitivities.

In a recent exhibition held in his native country which was documented in a book entitled Margiela, The Hermès Years, it was disclosed that he often asked the women working in his atelier and close friends to try on works in progress and hear their feedback. He would conduct six fittings for each ready-to-wear piece, an extensive amount, and often built in specific features he knew his customers would appreciate. One of Margiela’s signatures while designing for the house was a cozy tunic that could be layered in a host of different ways—giving the wearer agency over her look—and be easily pulled down off the shoulders and stepped out of so as not to disturb hair or makeup. From the start of Margiela’s time there, it wasn’t at all unusual to witness Asian women, shorter women, 50+ women walk his runway. It seemed so natural, so authentic because it was. It was an exercise in making women, many women, visible and comfortable above all else. It doesn’t get more modern than that.

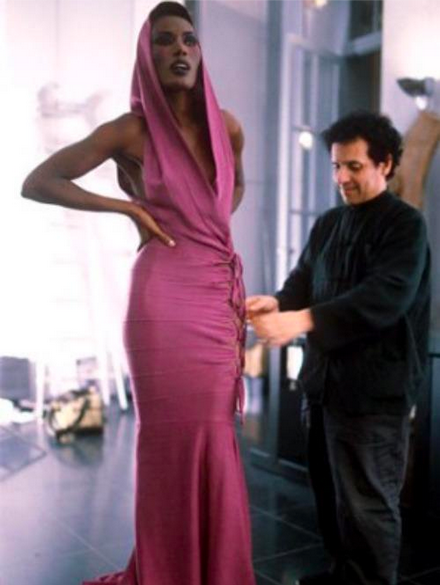

One got a similar feeling watching presentations held by the late, great Azzedine Alaïa. There were the midriff-baring, short-skirted dresses for the young, hot yoga devotees; longer dresses with skirts that floated just below the knee and slender sleeves for those approaching or beyond middle age who no longer wished to show their upper arms; the razor-sharp tailoring, crisp shirting and immaculate trousers for the women who didn’t prefer the traditional trappings of femininity at all. For a couture-themed photo shoot and accompanying behind-the-scenes video for W magazine in 2011, Carine Roitfeld had ensembles made for her at just about every significant couture house showing in Paris, Alaïa included. Alaïa painstakingly conducted the entire fitting from start to finish. Roitfeld noted how much extra work he was taking on by attending to his clients so closely and he responded, “Listen, when you look after clients, that’s how you learn. Because if you don’t see how a design is worn or what women want or how they want to wear it, you’re just designing in a void and that isn’t good.”

And that is just one of many reasons why the Tunisian-born couturier is so missed. Alaïa's garments were so remarkable because he respected women so deeply and honored their opinions. Lauded fashion journalist Cathy Horyn may have put it better than anyone else, “I didn’t know that he had designed garments for the girls at the Crazy Horse,” she said referencing the famed Parisian cabaret (known for its largely nude stage spectacles) during an interview in a short film on Alaïa directed by stylist Joe McKenna. “And I thought, God if you have to get in there and really measure those women, you’re really not worried about women. You’re not intimidated by them. You don’t have any fantasies about them. And that, we all know, is a problem with many designers, male or female. They have a fantasy about women that doesn’t jive with reality.”

Fashion, as a business, collectively asks for women’s money yet makes sure they are not involved in formulating the strategies or making the decisions that affect what gets produced for their consumption. Women make up a large portion of the garment trade, both at the luxury and mass levels, making them particularly subject to its injustices whether it is workplace harassment, lack of upward career mobility, unsafe--even deadly--working conditions or low pay. If fashion wants to address inequality, it needs to make robust, actionable plans that start from within where the problems it proclaims to be against are taking place in plain view.

Written by Martin Lerma